An Elmira Girl Goes to England

One of the more charming aspects of attending a women's college in the 60's, was the opportunity to go abroad for your junior year. I spent my junior year studying at Manchester University in England for the academic year 1964/65.

When I left Elmira, my art professor, Richard Cramer, said, "Don't forget to take your watercolors."

A friend of my father wrote this note on an article

about me in the local paper and sent it to him.

Every time I look at it, a tear comes to my eye

because I loved my father so much.

I sailed on a student ship (like a tub) arriving in Southampton. I took the train to Manchester. When I arrived at Ellis Lloyd Jones Hall, the residence where I was to live, I was greeted with: "Didn't you get our letter. We didn't want you to come until next week."

Me, standing in the Ellis Lloyd Jones Hall garden,

1964 and wearing my signature trench.

I signed up for art history and Shakespeare. Don't ask me why I took Shakespeare. I really don't like Shakespeare. (Are you permitted to say that?)

Soon I met a boy named Peter. He was on his junior year abroad from Amherst College studying American Studies. (Ironic, that, since he was in England.) We started to date. He had some interesting friends, including the poet, Tony Connor. Sometimes we would go to Tony's house to visit. Peter and I had a favorite place to go: Alderly Edge, a charming village in Cheshire outside of Manchester. We took the train.

Standing on the overlook in Alderly Edge.

During my time at Manchester I tried out for a play, "The Crucible," by Arthur Miller. I got the part of one of the girls who become hysterical. I was good at that. One of my lines was something like, "The rafters, it's in the rafters!" We performed this play at a festival in Southampton, England and won first prize. After the play someone said to me, "I wondered who that girl was with the 'farmy' accent."

I am on the left.

The Crucible won the trophy as

best production at the National Student

Drama Festival in Southampton, England.

My friend, Jamie Frucht, was living in London. I met her my freshman year at Elmira. Then she transferred to Antioch College. Jamie was a writer, and we were truly kindred spirits. We both had Advanced Placement in an upper class creative writing class. The class was taught by Brian Way, a poet from Wales. Jamie became enamoured of Brian. Jamie and I rode our bikes around Elmira laughing and trading puns.

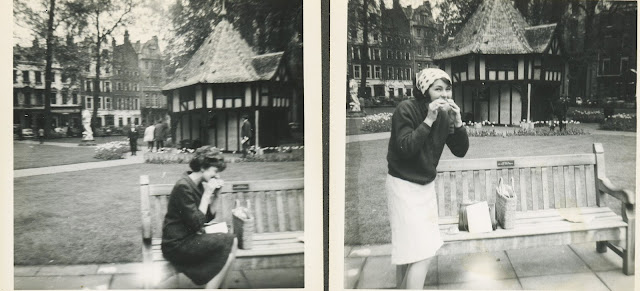

Jamie and I in London.

Jamie and I lost touch for many years. It was my fault, but we finally reconnected. And none too soon. A rare disease, Marfan Syndrome, ran in her family. Her father and sister died of it, and then Jamie died in 2004.

Jamie and I loved the movie, "The Red Desert".

In these pictures we are pretending to be Monica Vitti

who eats a sandwich with particular intensity in the movie.

This was the type of thing that we found to be funny.

Jamies was an incredibly wonderful and unique person. She lived in Oakland, California, and for the last years of her life, taught high school English there.

On the lawn of Bournemouth University

with Jamie's friend, Dianna.

On the rocky beach at Brighton, England.

Dianna, Jamie and I rented bikes and rode through

Thomas Hardy country, sleeping in the New Forest

where the wild ponies roamed

and on Brighton Beach.

During my time in Manchester, I travelled in Europe a lot, often hitch hiking with either Peter, or another Elmira student who was also at Manchester. During one 3-week trip, I was in Italy, Yugoslavia and Greece to name a few places on my itinerary. I became an intrepid traveler.

Sitting on a wall along the Arno River, Florence, Italy.

In the garden of the youth hostel where I stayed

in Florence.

Before I left for England, my mother gave me a pink umbrella.

Life Under A Pink Umbrella

Excerpts from an essay by Carol Markel, 1966

Published in

Sibyl, the Elmira College literary magazine

A year is made with foreign subtitles in cinematic progression. You are the director, who is directionless, but who depends upon the impulsive inspirations of time and circumstance, who sees reality with cinema eyes, and who turns experiences into scenes. Your actors move in and out of the set, uninvited but welcome; diverse actors of the burlesque and the tragic. You may plan, but plans turn into what might have been. Life continues, sometimes in vague slow movements of obscurity, sometimes with the sharp force of a revelation.

Therefore, a year continues to its physical end until the time comes to an invented wall and the places change into a new experience. You many gather the images collected on foreign soil. Your mind remembers its miracle of recollected sensations. You must crystallize the director's notebook.

A Beginning

"...there is an order in this world; there are distinctions, there are differences in this world, upon whose verge I step. For this is only a beginning." Virginia Woolf

Leaving. The departure, a gulf widening between the dock and the ship, the water growing larger, until it is borderless, and the days exist only for the sea and for the sky. We begin to realize the vastness of the world. The feathered noise masses in the wind, and the sun beats down on the deck, while waves pass without mercy. The sense of going, cuts into Atlantic waters, as we go only forward, moving out into the feeling of going away. Although the departure means an absence of one year, the affiliations are with the future. The ship moves out past the Statue of Liberty, under the Verazanno Narrows Bridge, out to sea toward Southampton, England.

And my life under a pink umbrella began. The showers came, bringing with them tiny particles of soot. Dirty rain. But one soon learns to live under an umbrella, peering up into the nylon shelter, keeping the world at a distance with swift jabs of the point.

Uniform rows of small, square, red-brick dwellings line the streets. The backs streets of Manchester. One is drawn to them to walk and to see. Images in color: red and brown-gray. Children play in the piles of crumbled bricks. They make me happy. A walk in an ordinary street. But I was looking for something else. I was not the health inspector nor the town planner.

A morning, perhaps in November, which has been clouded with shades of gray fog, is suddenly pierced by a perfect orange disc. When for an instant in the afternoon, the sky was clear, I could see the distinct outline of the structures and realize the architecture. They were like small revelations on a Sunday morning, walking the heart of the city in Albert's Square.

Or the blind pea soup fog in autumn which changed the familiar streets into black tunnels as if we were in a city of impenetrable dust.

Life, I whispered and ran my fingers along the brick wall on Talbot Road.

Life, and ran through rained out November twilight to the black, shiny gate.

This city, laid out in crumbling brick boxes with chimneys as chess kings,

crowned and jutting, especially just in the evening when I was returning.

The nightcomers, the men going past on a grating red bus splashing the gutter.

Workers intent on the road riding home on bicycles steady and peddling fast.

Brick wall along Talbot Road, skims the evening toward the black gate.

Woodcut by Carol Markel, 1966

Cheerio, mes amis!